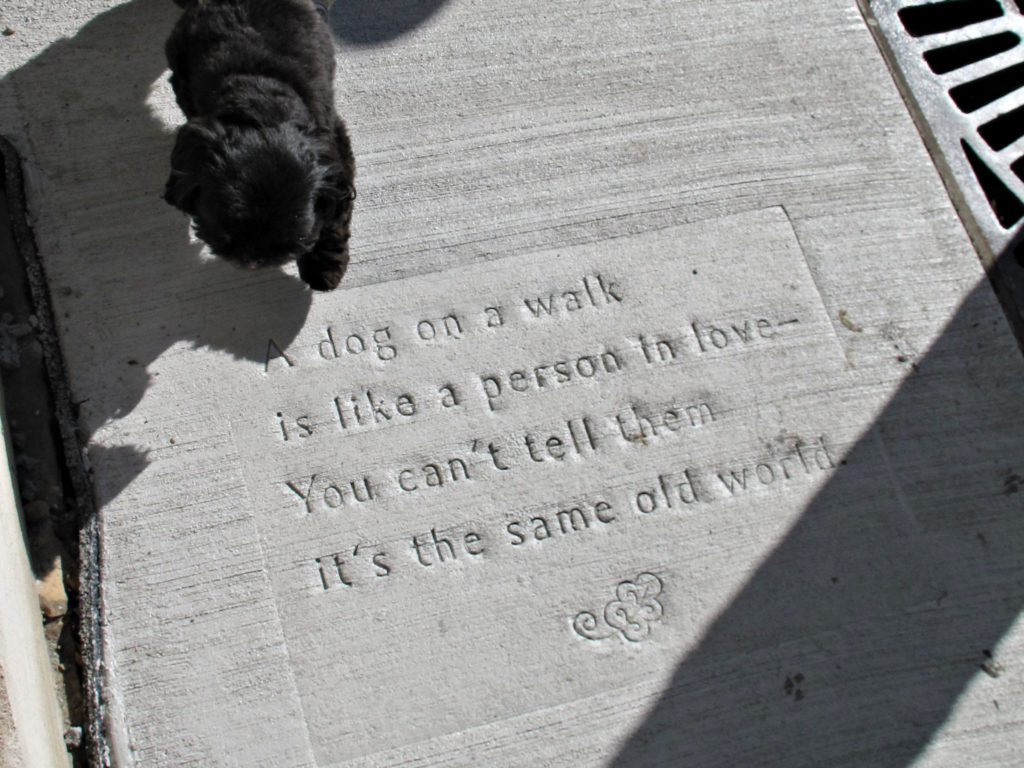

Poem by Pat Owen, photo by Mike Hazard.

Since 2005, the City Artist program of Saint Paul, Minnesota has provided a model for an innovative public-private partnership between the City of Saint Paul and Public Art Saint Paul, a non-profit organization. City Artists are integrated into the daily and long-term workings of the city to create art out of life-sustaining municipal systems. Artists advise on major city initiatives, lead their own artistic and curatorial projects, and have dedicated workspace within the Department of Public Works so they can freely collaborate across city agencies.

Marcus Young, a behavioral and social practice artist, was a City Artist from 2006 to 2015. Following the conclusion of his term, Marcus reflects on his near-decade experience working within this collaboration between artist, city government, and arts nonprofit.

For more than nine years I was City Artist in St. Paul, MN. One of the many things I learned from that experience is that there is a lot of room for artists in city government. The room I’m talking about is a creative conceptual space, mostly hidden and yet to be fully explored. You can barely see it from the perspective of traditional public art processes. You certainly would have a hard time seeing it from the gallery or museum. You can easily see it with the beginner’s mind, sitting alongside city staff for a length of time, with neither artist nor staff beholden to a fixed agenda, and with an outsider’s heart that yearns for an artistic belonging not usually recognized in officialdom.

This will sound over-romanticized, but the magical feeling of those nine years was as if I had walked out of some mysterious back door and onto a very big and open field. I would look around astounded, thinking, “Do other artists know this is here? Does anyone know this is here? This place to play and roll around in. This beautiful place with very different and few rules, at least that I know of. A new and open space full of possibility.”

When I would come back from that daydream world—to my cubicle (yes, I had a cubicle as City Artist), to the emails, to the seemingly immovable city, to my doubting heart—I would remember the old voices: “Is this the life we want for ourselves?” or “How can place be more meaningful?” or “How do I belong here?” We all have this basic yearning in life. I felt it strongly as an artist in residence in the context of the city.

Maybe that’s why, wandering between these two perspectives—the wonder-filled discovery of someplace new and accepting, and the old, familiar heartache of not belonging—I reached out to Mierle Laderman Ukeles for some guidance and reassurance. I think it was 2007. When I walked into her downtown office at the New York Department of Sanitation, I was in part representing my own Public Works Department, artist to artist and city to city. It was a heartwarming and strange moment, and Mierle so welcomingly and artfully marked that moment. Her first words after we sat down were, “Are we the only two in our species?”

How I came to be there at that moment and a City Artist for nine years belongs in great part to an innovative partnership between a small nonprofit and a small capital city on the Mississippi. In 2005, Public Art Saint Paul, with the support of the City of Saint Paul, led a pilot program to invite artists, one at a time, to explore how to do work seated at the big table of the city. Each artist had up to 18 months at a one-third time contract. I was the second artist, and by the end of my pilot term, I knew that a different model of how artists can work in the City was achievable; a long-term and deeply integrated approach. The artist is paid by the nonprofit and is housed in the City offices—in my case in the Public Works Department—but there is the freedom to work with anyone at the City. From 2008, I started working near full-time and developing the idea of “city art”—art that is made by artists placed far upstream in the city-making process, art that is not put into the city, but made out of the living systems of the city.

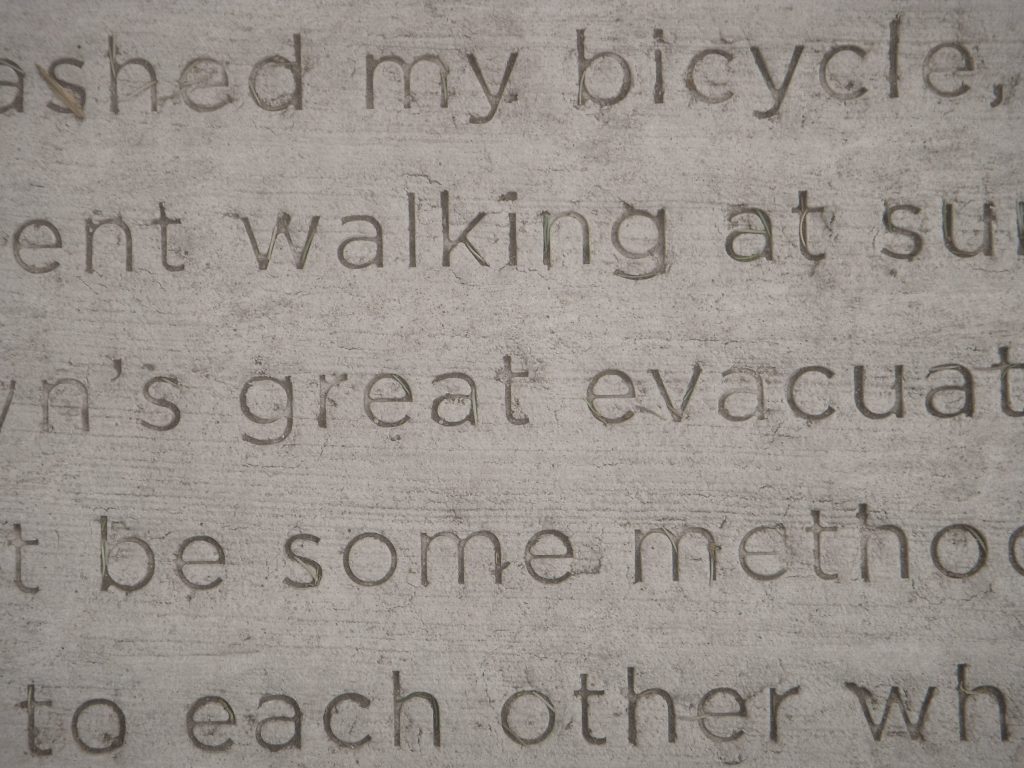

Detail of a poem by Anna Everett Beek, installed as part of Everyday Poems for City Sidewalk.

My approach to city art was to work as a discreet yet long-term guest, meaning I was there long enough to understand the vision and culture of the city, even embrace and practice it, but came at it from a very different place. As a guest, I did need to seek permission at some level to do the work, but more often than not I found a great permissiveness and a true desire to invite artistic thought into many areas of city work.

Another way of explaining the model is like a virus free-floating in the systems and culture of the city, deciding for itself where to go, what to do, and not following a predetermined path or RFP. The virus needs a healthy host. It is a part of the host but also of itself, seeking a symbiotic balance. If the virus analogy sounds too negative, the then-St. Paul Mayor Chris Coleman can come to the rescue to say, “A virus at the right dosage is an inoculation.”[i] A third way of explaining the model is through its shape or diagram—a triangle—with the corners being the mediating and supporting arts nonprofit, the host city government, and the individual viral artist.

The clearest example of city art is the work we made called Everyday Poems for City Sidewalk. This is an ongoing systems-based work of art that re-imagines St. Paul’s annual sidewalk maintenance program as a publishing entity for a city-sized book of poetry. Integrated with the essential service of replacing broken sidewalks, the poetry service has installed more than 750 poems reaching all corners of the city. One result of this long-term commitment is that, as of this writing, 17% of St. Paul city land is within a two-minute walk of a poem created by this single work of art. (These figures are from the project’s start in 2008 through 2014. The project has continued since then, and the figures are much higher now.) The work aspires to pave every city street with poetry. Every year St. Paul residents can submit poems to a contest as a way of collectively writing the book in which they live.

The value of this work is not only the number of poems but that it opened that mysterious back door onto the newly discovered field, and hopefully keeps open the way for other artists and works to follow. A little gesture of a work of art such as this carried out systemically points to the endless possibilities of art making in the hidden everywhere. In this unlikely place of St. Paul, which I have heard jokingly and lovingly called “a little eddy of nothingness,” I believe we have invented a new way of being an artist, a close kindred species to Mierle and perhaps others, but unique and worthy of closer examination. There is a lot of room for more of our species and great potential for the specific type of space we discovered.

My near-decade as City Artist has just ended. It’s a good time for a first look back on this exploration and to see what happens next to this model of art making. I see the first ten years of the program as a research phase that has posed essential questions if it is to go forward. Can the program formalize yet keep what was agile and liberating? Can it figure out the sticky issues such as ownership of the art made through it? Can it reflect and evaluate more carefully and openly this work that is hard to talk about?

[i] Tillotson, Kristin. “Cities Turn to Artists as Urban Troubleshooters.” Star Tribune. Star Tribune, 16 Mar. 2013. Web. 11 Apr. 2016 http://www.startribune.com/twin-cities-turn-to-artists-as-urban-troubleshooters/198558491/.