Participants in ABOG Fellow Suzanne Lacy’s project “De tu Puño y Letra” in Quito, Ecuador. Photo by Christoph Hirtz.

Editor’s Note

___

This excerpted version of Willsdon’s essay about curating the retrospective,

Suzanne Lacy: We Are Here, provides insightful ramifications for exhibiting socially engaged art in museums more generally.

With Rudolf Frieling and Lucía Sanromán, I am co-curating a retrospective of the art of Suzanne Lacy. We are, as I write (in October 2017), nearer the beginning of our process than the end. The exhibition, a collaboration between the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) and Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (YBCA), is due to open in San Francisco in Spring 2019, and it has been a bit more than a year since our work began in earnest. The project poses some rare challenges to museum protocols. We need to present Lacy’s collaborative, ephemeral, and context-specific practice (nearly five decades of it) responsibly and in full, in an environment for which it was not intended and which was not designed to support it. Although the exhibition has the standard goals of a solo retrospective — to collate and historicize the artist’s works, provide an optimal experience of them, assess their abiding value, and make them public in new ways — achieving them will require that we apply some non-standard methods. While this type of retrospective is a familiar format, Lacy’s art requires that some of its basic assumptions be rethought. There is, for one thing, a question of materials: what set of acts, objects, and agents constitutes a work? There is also a question of authorship: what does it mean to apply the single name “Suzanne Lacy” to an exhibition of projects created by so many participants and collaborators, including many other artists, and how should those others be involved and recognized now? And there is a question of history: how can we look back at these projects, which were impelled by the politics of particular times and places, and find ways to experience today what they have meant and still can mean in our present? There are questions of aesthetics as well: what does it mean to reconcile such a practice with the museum’s predominant art history (of painting, sculpture, and photography)? And how should this work be produced and presented as art? It is still rare, in art museums, to face such questions, but it is becoming less so. In recent years there have been a number of artists working in socially engaged, process-driven ways who have received solo museum shows: for instance, Allan Kaprow, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Mel Chin, and Paul Ramírez Jonas. There was also a partial survey show focused on Lacy herself in Milan in 2014. Certainly, solutions developed for these examples and other projects may be applied to ours, just as the solutions developed for our project may, we hope, be applied to others in the future. As curators of Suzanne Lacy we have an opportunity to contribute to a nascent, broad, collective effort to make time and space for art such as hers in museums, which is to say in the public history of art.

[ … ]

Lacy’s projects were not designed for museums and vice versa. One way to make it possible to show such projects in an optimal way in museums would be to design and create new manifestations of those projects for the museum. Down this path we meet a fundamental question: what would it mean to produce a retrospective that is guided not by the task of remembrance but by the task of creating an exhibition that is an event in the here and now (of 2019), supported by anterior materials? This would lead us to take, as a starting point, the specificity of our “now” — politically, culturally — and the specificity of our institutional settings.

[ … ]

[C]urating Suzanne Lacy requires us to ask some questions for which existing models of curating performance (or video, drawing, archives, etc.) do not provide answers. How should those participants be involved and represented in both the exhibition-making process and its presentation? And beyond this, which aspects of any given project still live? And which can be or should be brought to life?

So far, we are asking these questions primarily with respect to The Oakland Projects (1991–2001), a series of projects over ten years that embody a continuous, evolving set of concerns — especially in relation to youth, race, and public policy. We chose to focus on The Oakland Projects, of course, because they are the major body of work that Lacy created in the San Francisco Bay Area, so their history is local to us. Inasmuch as reassembling any of Lacy’s works of collective action might mean drawing again on the experience and understanding of those who participated originally, we wanted to treat The Oakland Projects in a deeper, more expansive way.

[ … ]

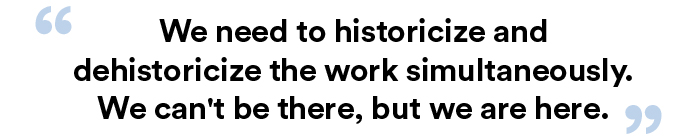

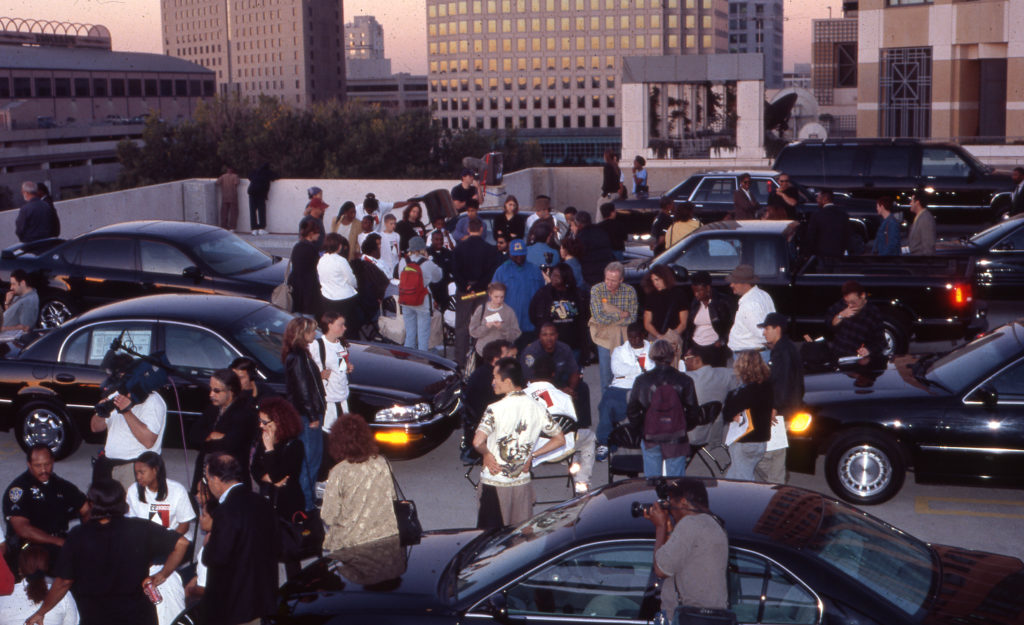

“Code 33: Emergency, Clear the Air,” 1999, by Suzanne Lacy, Unique Holland, and Julio Morales, was one of eight major works in Lacy’s series “The Oakland Projects.” Photo courtesy of Suzanne Lacy.

[O]ur approach in this first phase has been this: we have distanced ourselves as curators and Lacy as artist from the process, and instead engaged two researchers, both still Oakland residents who were collaborators on The Oakland Projects and who have had since the 1990s roles that allow them to bring relevant perspectives and expertise (from outside art) to bear on the research process and goals. Unique Holland first participated in The Oakland Projects as a fifteen-year-old and became, in time, a named artist-collaborator, and until recently worked as director of communications and public affairs for the Alameda County Office of Education. Moriah Ulinskas was a youth media producer on Code 33 and is now an archivist and researcher in Public History at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Each is pursuing a different, complementary research path. Holland is describing a set of relationships between individuals, representing the participant groups that stand behind The Oakland Projects. Ulinskas is describing a set of institutional relationships with youth policy at the center — in some ways, this can be a portrait of the institutional infrastructure of Oakland in the 1990s; the organizations (city, schools, funders, etc.) that were comprised by the landscape into which Lacy’s The Oakland Projects intervened. In this way, we are inviting perspectives that are at the same time inside and outside the frame of The Oakland Projects. We want to surface perspectives that are not aligned with ours nor Lacy’s, perspectives that are not even framed by the projects themselves.

We have come to see Oakland as the protagonist of The Oakland Projects. If the central issues were youth, race, and policing, we are now asking how these issues have and have not changed since the 1990s. Oakland has changed — not least in terms of its demographics and the active organizations and agencies that function in support of public life. The public conversation about race and society has changed as well. The Oakland Projects were devised and produced in response to representations, in the media and politics, of teenagers as a threat. Having identified the context in which The Oakland Projects originated, we now ask what is the environment in which we can re-present them now, in 2019? What can it mean and what will it take to update them, and who should be the agents of this updating?

[ … ]

The motivation for “rethinking” a past work (Lacy prefers to speak of it in this way, rather than using terms such as re-creating, revisiting, reworking, etc.) may be either or both of two things: political timeliness or artistic potential. In the course of the conversations at ICI*, she touched on the fact that she sees new or unrealized artistic possibilities in the idea or premise of such rethinkings; that it seems valuable/appropriate to return to earlier projects taking into account a different political context — new reasons, new needs. We do not yet know whether any works in the retrospective will be subject to such revision, but we do know that Lacy is currently, and probably permanently, disinclined to rethink The Oakland Projects in this way, at least through her own agency. This may be partly because the youth experience has changed so much, and partly because of current political conditions. Today it is impossible that a white artist could directly choreograph such interactions and representations the way she did in the 1990s.

[ … ]

“Code 33: Emergency, Clear the Air,” 1999, by Suzanne Lacy, Unique Holland, and Julio Morales. Photos courtesy of Suzanne Lacy.

Related to Oakland, [City of Oakland’s Cultural Affairs Manager Roberto] Bedoya (and others) pointed to displacement as the most urgent social and political issue now, characterizing it as a current form of violence and as an erasure of black social life in the city (over the last ten years there has been a 20 percent decline in Oakland’s African American population and a rise in its Hispanic population). The complexities of accounting for the shifts in national and transnational youth culture in gentrifying cities such as Oakland — including anti-youth government policies, media politics, youths and violence (as recipients and perpetrators), creative expressions and protests, the rise of technology, and new forms of onslaught and resistance to black culture — offer a monumental example of the challenges of rethinking Lacy’s socially engaged work. The strands of such conversations lead toward a single question or proposition: what if a retrospective of Suzanne Lacy were to take place as fully as possible in the present? Are there ways in which this could be a “living exhibition” that aims to address contemporary issues, or abiding issues in their contemporary manifestations? This is a matter of making it new, for our time and place. How can we avoid the sense of “we weren’t there” that can be induced by an exhibition of past actions (the risk of exhibitions of performance)? The answer lies in presenting two contexts at the same time, in being able to hold in our minds the reality that the work is dated and yet persists. These are art projects that are not over; you can visit them and their legacies at different points along the way, and the issues that prompted them — violence against women; race, youth, and the state; immigration; the culture of the white working class, and other matters — are as present today as ever. We need to historicize and dehistoricize the work simultaneously. We can’t be there, but we are here.

[ … ]

In the exhibition’s initial San Francisco presentation it must be reconciled within two very different institutions: YBCA and SFMOMA. [ … ] YBCA is animated by an aspiration to social remedy. This is rooted in its origins, having emerged from the ruptures caused by the redevelopment struggles of the 1960s and 1970s. Today YBCA tells its story in the language of civic and community action. It is also a non-collecting institution (therefore not anchored by material art objects) and a multidisciplinary and solely contemporary venue at which live programming is at least as present as visual art. Suzanne Lacy will be relatively at home within its program, which tends to explore political, civic, and pedagogical practices: practices that in various ways are leaving art. This year, for example, they have presented the work of Lynn Hershmann Leeson, Tania Bruguera, Erick Meyenberg, Estudio Teddy Cruz + Fonna Forman, and Damon Rich and Jae Shin (Hector). Given this context YBCA is a more hospitable environment for Lacy’s practice than SFMOMA. It is more accommodating of live experience, claimed results, and sources outside art — indeed, YBCA is most comfortable with these dimensions of art practice. We have both venues to contend with, and we face the question of how to organize a single exhibition across them. Our plan is to reassemble The Oakland Projects at YBCA — perhaps alongside The Skin of Memory (1999) and the projects about youth issues that Lacy organized in Vancouver, Turning Point (1995) and Under Construction (1997). These projects originated in the same period and among Lacy’s works most programmatically connect art to public policy. Returning Lacy to art at YBCA is a movement toward the live, the present, and the political. This context asks most of us, as curators, in terms of reassembly and translation of Lacy’s work for the present. It asks that we make good on YBCA’s claims to civic engagement and art for and in our time. And of course presenting The Oakland Projects not in Oakland but in the neighboring city of San Francisco presents its own questions. For instance, what is the responsibility of the neighbor?

[ … ]

SFMOMA seems like a less hospitable context in which to consider Lacy’s practice as art. To introduce Lacy’s art here is to ask of it some questions which are not so often asked, questions about aesthetics and art history. And what aesthetics and art history in particular? SFMOMA’s predominant aesthetic regime comprises late modernist abstraction, expressionist figuration, post-Pop and post-conceptual painting, plus various traditions of photography (including social documentary and vernacular, but excluding, at least until very recently, uses of photography in conceptual art). SFMOMA is primarily designed with the interests of these forms in mind. The museum’s program does include media art (Rudolf Frieling’s sphere) and performance and public dialogue (parts of my sphere), but these are less visible and, let us admit, relatively minor areas of activity. Is the project of a solo retrospective of an artist working in these minor forms an elevation of those forms? A departure for SFMOMA? An experiment in performing a different institutionality? Or even an attempt to confront this genre of art practice with the histories of art since the 1960s that museums of modern and contemporary art primarily present and acquire? Yes, it is. But it is also an elaboration in quite different directions of the impulse behind the major, resident forms.

“Code 33: Emergency, Clear the Air,” 1999, by Suzanne Lacy, Unique Holland, and Julio Morales. Photo courtesy of Suzanne Lacy.

If, as I suggested, the production of forms is as much a part of Lacy’s work as is the facilitation of process, we have to ask about the aesthetic character of those forms. The museum should be the place where this can become visible in a new way, a way that extends its history of art. Introducing Lacy to the predominant aesthetic regime of SFMOMA, we might find both difference and complementarity — with California Conceptualism, no doubt, and with the picturing of the topography of the West and vernacular traditions (which is to say, practices that are local, popular, and utilitarian), with the exploration of the post-Pop body, and latterly, at least, the “face of our time” typologies of photographers such as August Sander and Zanele Muholi that we see in the Brierfield (The Square and the Circle) and Quito (De tu Puño y Letra) projects this year. Let’s even suggest that Lacy’s art shares a chromosome with SFMOMA’s most prevalent aesthetic regime: the post-minimal aesthetics of artists such as Ellsworth Kelly, Sol LeWitt, and Richard Serra. Think of the use of primary colors — for Lacy, especially red and yellow, plus black and white — from In Mourning and Rage, through Whisper, the Waves, the Wind, The Crystal Quilt, and so many other projects to the present. Think of the use of geometry and repetition. There is perhaps (we will see) an aesthetic complementarity combined with an essential difference, which is to do with the contingency, mobility, and agency of the forms in Lacy’s art — since, of course, her forms are composed of people, not inanimate materials. There is a tension between the regimented and the unregimented. Lacy’s monochromes and geometries contain an ungovernable element, an element of disobedience. The museum should offer the opportunity to foreground this. Lacy is the author of the aesthetic (though it can be developed collaboratively with other artists, e.g., Leslie Labowitz or Susan Steinman), but it admits the lives of others. She may direct them to wear a certain color and walk in a straight line, and if they do not quite do this, so be it. This is post-minimal art that vibrates with the contingency of the social. Imagine Between the Door and the Street as a vast yellow monochrome, torn into strips and distributed among women in a Brooklyn street. Beyond matters of shape and color, think about how the social functions differently, how labor is structured in Lacy’s process compared to LeWitt’s, how public space, and time, is produced differently in her work compared to that of Serra — and, of course, think of Lacy’s advocacy for “new genre public art” in Mapping the Terrain. There she struck beyond a debate on public art in the United States, on plunk art, within which Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc (1981) was the lead example. Lacy does not leave art, her practice is a non-art activity of a different order to art such as that on view at SFMOMA. It is that same art, but agitated by life. Our task, with the artist and others, is to reconcile this art to the museum and, more importantly, reconcile the museum to it.

In any encounter with art such as Lacy’s, there can be a feeling that something is missing. Some integral act, object, or agent is either no longer present, now out of sight, or still to be produced. It is an experience that may seem, unsatisfyingly, more like encountering life than art. We know that, with all variants of post-conceptual art practice, it is part of the work that some element is evidently absent. Yet the feeling of absence in an encounter, at any moment, with Lacy’s practice is different, and may seem lacking in a more matter-of-fact way. The audience for this art may feel not that a full and satisfying art presence is impossible but that it has been possible, and we merely missed it. That is a trap. Encountering these projects, in any of their forms, we are no more present to ourselves and to each other than in life, but also no less so. No particular way of representing this work can capture it, because they all do. Nothing is fully present, and nothing can be fully absent. The work is not over. Our task is neither to deny nor collapse the gaps, in time and space, spanned by this practice, but to represent what is in-between and leave it open for what is to come — not least for artists coming up who may find here a curriculum for their own work. What must be there is the agitation — that cannot be missing. It is going to be hard to evoke the discord and friction proper to process and the agitation proper to form. Without not only the presence but also the evidence of this agitation, the project will have failed.

*The ICI is the Independent Curators International, which co-organized and hosted a two-day convening of curators, critics, and artists in New York on questions of museum presentation. (ed.)

Dominic Willsdon is the Leanne and George Roberts Curator of Education and Public Practice at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Read the entire essay here.